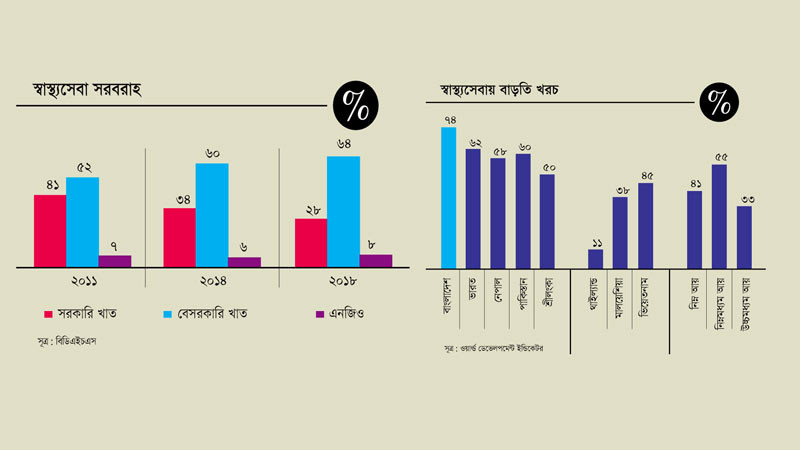

Ensuring basic health facilities is a key component of Bangladesh’s health policy, which designates the private sector and NGOs as supplementary providers. Despite the development of health infrastructure across the country, inadequate facilities and services have led the public to place greater trust in the private sector. Currently, more than 70 percent of healthcare is provided by private institutions, although this comes at an additional cost. As a result, the public sector’s lack of capacity has created a challenging situation in dealing with COVID-19.

Stakeholders report that mismanagement and lack of planning have hindered the effective utilization of government healthcare infrastructure. Despite having the infrastructure, there is a shortage of doctors in health centers, and many recruits are frequently absent, particularly in remote areas, causing significant suffering to patients. Additionally, government healthcare centers lack sufficient medical equipment and instruments, rendering the existing infrastructure ineffective for patient treatment.

Conversely, many people cannot afford the high costs of private sector healthcare. Analysts highlight that this structural weakness in the national healthcare system has become most apparent during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, impacting patients, doctors, and other related individuals.

Experts note that while the public sector globally leads in managing COVID-19, Bangladesh is no exception. However, the epidemic cannot be tackled by infrastructure alone. The high cost of private healthcare is inaccessible to people of all classes and occupations, revealing a structural weakness that complicates epidemic management.

Dr. Mozaherul Haque, a former advisor to the World Health Organization in Southeast Asia, stated that a patient incurs a minimum cost of Tk 2 lakh at a private hospital, covering expenses such as water, electricity, and bed charges. Depending on the patient’s condition and disease, this cost can exceed Tk 10 lakh. As private centers are business-oriented, this mentality is evident in their treatment approach. While private healthcare dominates globally, their healthcare management is generally much better.

Dr. Haque also noted that government healthcare centers are often preoccupied with procurement activities, with many new but questionable quality buildings being constructed. There is corruption in the procurement of devices and materials, and with insufficient manpower, the quality of available personnel is also questionable. These issues reflect a structural weakness.

The latest Bangladesh Health Facility Survey by the National Population Research and Training Institute, published in 2020 by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, indicates that Bangladesh spends 3 percent of its GDP on health management, which is low compared to peer developing countries. Only 1 percent of this funding comes from the public sector, with the remainder provided by private and development agencies. Consequently, private health management plays a crucial role in the country’s healthcare success.

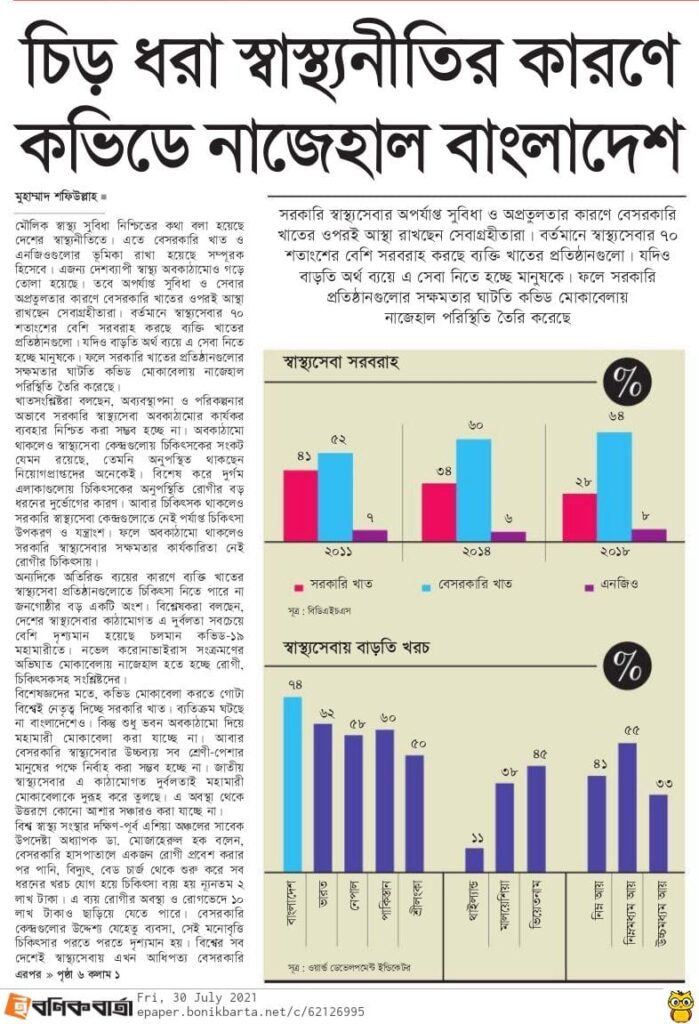

However, according to the World Development Guidelines, people are incurring additional costs when taking private healthcare. Citizens are spending 74 percent more on medical expenses, which is higher than in other Asian countries. The additional cost of treatment is 62 percent in India, 58 percent in Nepal, 60 percent in Pakistan, 50 percent in Sri Lanka, 11 percent in Thailand, 38 percent in Malaysia, and 45 percent in Vietnam.

According to data from the 2016 Khana Survey, 46 percent of healthcare institutions in Bangladesh are privately run. Generally, secondary and tertiary level medical services are dominated by private management. Bangladeshis spend five times more money in private institutions than they do in government institutions. The growth of private healthcare is increasing day by day.

Every year, the number of private healthcare institutions in the country rises. In the 1990s, 384 private hospitals were established across the country. According to a government estimate, as of June 2018, 16,979 privately owned healthcare institutions have been established. Among them, there are 10,291 diagnostic centers, 4,452 hospitals, and 1,397 medical clinics. Additionally, there are currently 839 private dental clinics in the country.

Experts say that healthcare in the country is almost entirely in the hands of private institutions, which does not bode well. Large industrial groups in the country began investing in healthcare mainly since the 1980s. After the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, government healthcare institutions in Bangladesh, like in many other countries, stepped up. However, the poor condition of the government’s healthcare department in dealing with the coronavirus highlights the lack of resources and service quality.

Public health expert and Director of the Directorate General of Health Services (Disease Control), Professor Dr. Be-Nazir Ahmed, said there are serious questions about the quality of treatment in government hospitals. Business has become more important than service. Although the cost is high, people are less likely to go to government hospitals because they face harassment there.

Professor Syed Abdul Hamid from the Health Economics Institute of Dhaka University believes that people turn to private institutions after being deprived of services in government institutions. He said, “Although the cost is high, due to the improvement in economic conditions, people take private healthcare despite the cost. If harassment is not stopped in government healthcare institutions, people will continue to go to private institutions. The government is not paying enough attention to healthcare. The issue of health management remains neglected by the government, which is reflected in the annual budget allocation. The population has increased day by day, but the scope of government healthcare has not expanded. At the same time, there is a lack of planning.”

The latest health bulletin published by the health department in 2019 states that there are 654 upazila health complexes and secondary and tertiary level government hospitals in the country, with a total of 53,448 beds. There are 1.55 doctors for every 10,000 people. However, there are 6.73 doctors for every 10,000 people in general. Government hospitals have 3.30 beds for every 10,000 people, while private hospitals have 5.53 beds. In 2018, government healthcare institutions provided outpatient treatment to 60 million people at the secondary and tertiary levels, outside of primary healthcare or community-based healthcare. Additionally, 1,897,833 people were admitted, and 2,508,000 people received emergency treatment.

According to government data, COVID-19 patients are being treated in 131 public and private hospitals across the country. The number of government hospitals outside Dhaka is higher. However, hospitals outside Dhaka and other major cities lack intensive care units (ICUs), high-flow nasal cannulae, and other emergency services. Fifty-two public and private hospitals dedicated to COVID-19 do not have ICU facilities, and half of the country’s districts lack this facility under government management.

The data also indicates that 16,036 general beds have been allocated in public and private COVID-19 hospitals across the country, with 70 percent of these beds occupied by patients as of yesterday. Of the 1,314 ICU beds, 83 percent were occupied by critically ill patients. Currently, there is a crisis in the treatment of COVID-19 patients in the capital. Officially, about 20 percent of general and ICU beds are vacant, according to the health department. However, in reality, relatives are moving from one hospital to another seeking ICU beds. The crisis has also begun to affect private hospitals.

Meanwhile, 70 percent of the patients admitted to government and private hospitals in the capital for COVID-19 treatment come from outside Dhaka. Due to the lack of emergency treatment at the district level, these patients are being brought to Dhaka out of necessity. Public health experts suggest that there would not have been such a rush of critical patients if necessary treatment had been ensured at various levels from the beginning.

Professor Dr. Abu Jamil Faisal, a member of the Public Health Advisory Committee of the Department of Health, said, “The issue of healthcare has been neglected for a long time. Even if there is a minimum plan, it has not been implemented. It appears that there are buildings but not the necessary services. Again, there are necessary parts but no manpower. Even when everything is in place, people are not receiving services in a timely manner. Despite one and a half years passing since the start of the pandemic, government agencies have not ensured the provision of emergency treatment.”

Dr. Rashid-e-Mahbub, former president of the Bangladesh Medical Association, said, “Our infrastructural weakness in the public sector is significant. There are buildings but no machines. Even if there are devices, they are not used, meaning the capacity is not being fully utilized. The problem lies in planning. There would not have been so many problems if we had planned adequately for the times. At the upazila level, infrastructure is in place and manpower like doctors and nurses may be provided, but the effectiveness cannot be ensured without proper oversight and concerted effort. There is a serious deficiency in these matters.”

Pointing out that the private sector operates without sufficient regulation, he said, “There is no one to supervise this situation. As a result, excessive profiteering and corruption have engulfed the private sector. These issues are more pronounced during the COVID-19 crisis because it is an emergency service disease. The existing healthcare system in the country is not equipped to handle emergency services effectively. The government now needs a commission to reform the health sector.”