The Ganges River originates from the Himalayas in the Indian state of Uttarakhand and flows over the Gangetic Plain region into the Bay of Bengal. A tributary of it joins the Mahananda and enters Bangladesh as the Padma, which flows up to Goland in Rajbari. This international river carries numerous small particles of plastic from upstream, posing a serious threat to the environment and human health. This information has emerged in two separate studies conducted by researchers in India and Bangladesh.

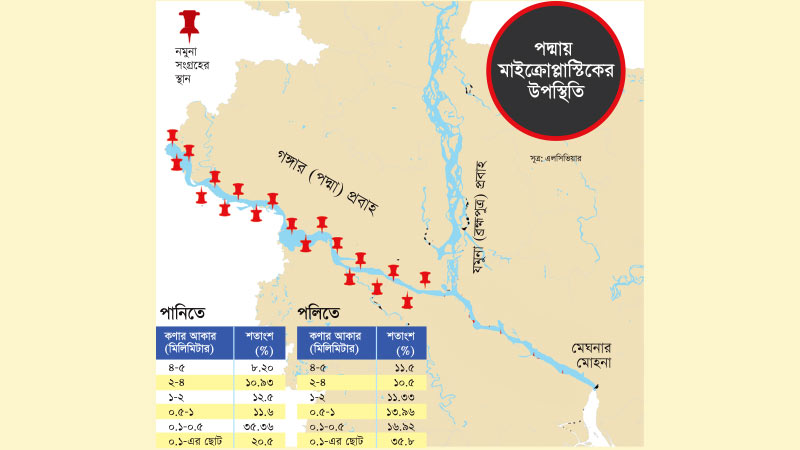

A research paper titled ‘Distribution of Microplastics in Surface Water and Sediment of the Ganges River Basin to Meghna Estuary in Bangladesh’ has recently been published in the Netherlands-based journal Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety by Elsevier. The research was conducted with water and sediment samples from 30 locations from the border of Chapainawabganj to the Meghna estuary in Chandpur. It reveals the presence of tiny plastic particles everywhere from the Indian border to the confluence of the Brahmaputra upstream of the Padma and from there to the Meghna estuary at Chandpur.

One of the research team members was Professor of Environmental Science at Jahangirnagar University, Shafi Muhammad Tariq. He stated to Banik Barta, “The Ganges or Padma river passes through many cities and industrial areas, so microplastics are found in it. Various studies have revealed that this is also the case in parts of India. We aimed to determine whether there is a higher concentration of microplastics upstream or downstream in the river in Bangladesh. The study found tiny plastic particles of different colors and sizes, with the rate of microplastics varying across different locations.

According to the study, a minimum of 14.3 to a maximum of 107.3 microparticles (particles smaller than 5 millimeters) were found per liter of upstream water, averaging 50.9 particles per liter. An average of 64 small particles were found per liter of water in the upstream area. Similarly, the amount of small plastic particles per kilogram of upstream sediment ranged from 823 to 6,143, with an average of 2,953. In the downstream area, 1,456 to 6,476 small particles were found per kilogram of sediment, with an average of 4,014. These microplastics were found in eight different colors.

Microplastic sizes are categorized into 4 to 5, 2 to 4, 1 to 2, 0.5 to 1, 0.1 to 0.5, and 0.1 millimeters. Depending on their size, these small plastics can be very harmful to nature and the environment. The majority of microplastics found in upstream water are between 0.1 and 0.5 millimeters in size, accounting for 35 percent. Additionally, 21 percent are smaller than 0.1 mm, 12 percent are between 1 to 2 mm and 0.5 to 1 mm, 11 percent are between 2 to 4 mm, and 8 percent are between 4 to 5 mm in size. Similarly, microplastics smaller than 0.1 millimeters were most common in the water of the upstream area, accounting for 26 percent of the total microplastics. The most common microplastics found in upstream and downstream sediments were less than 0.1 millimeters, accounting for 36 and 33 percent, respectively.

The study revealed five types of tiny plastic particles found in river water and sediment: plastic fibers, fragments, thin coatings, miniature pellets, and ultrafine balls. Small grains were also found in water and sediment at some locations. Among these, fragmented particles were the most common in the upstream area, accounting for about 44 percent. Following that, plastic fibers accounted for 41 percent, thin coatings and fine balls accounted for 6 percent each, and shoal particles accounted for 3 percent. Similarly, the fraction of plastic was high in the upstream water, accounting for 41 percent. Among other microplastic types, fibers comprised 31 percent, thin films comprised 18 percent, balls comprised 6 percent, and silt comprised 4 percent in the water samples. A large amount of fragmented particles (45 percent) was also found in the upstream sediments. Among others, fibers accounted for 32 percent, thin coatings for 9 percent, balls for 8 percent, and bran and grains for 3 percent each. In the sediment of the downstream part of the river, 46 percent of fibers were found, along with 25 percent of chunks, 12 percent of thin coatings, 8 percent of grains, 7 percent of balls, and 3 percent of bran.

Researchers state that most of the microplastics were small particles, contributing to plastic pollution in the Ganges river basin. These microplastics come from a wide variety of sources including thin plastic packaging films, bags, packaging materials discarded by humans, plastic waste, and skincare products. Some also originate from laundry detergents.

A study conducted by researchers in India a year ago on the presence of microplastics in the water and sediments of the Ganges has also been published by Elsevier. Titled ‘Preliminary Report on Microplastics in Tributaries of the Upper Ganges River Along Dehradun, India: Qualitative Estimation and Characterizations’, it highlights the presence of microplastics in the water and sediments of the Ganges River’s tributaries (Suswa, Rispana, and Bindal) in Dehradun, India. An average of 7,200 to 16,400 small plastic particles were found per kilogram of sediment from the sample collection sites, with every liter of water containing 2,800 to 4,200 small particles. Plastic fibers accounted for 41 percent of the particles found in water and 38 percent of those found in sediment.

Microplastics are an ’emerging’ pollutant in the environment, identified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a serious public health concern. The agency states that exposure to microplastic particles has human health implications. These particles enter the human body through the environment, food, water, and air. Moreover, microplastics in water can either float or sink based on the concentration, duration, and degradation rate of the material. Chemicals associated with them are also hazardous to aquatic life, severely affecting ecosystems, biodiversity, and human health.

ASM Saifullah, Chairman of the Environmental Science and Resource Management Department at Maulana Bhasani University of Science and Technology, has been researching small plastic particles in the environment and other environmental issues for a long time. He told Banik Barta, “The daily plastic we use is not properly managed. After being discarded, disposable plastic somehow ends up in the river. And if there is microplastic upstream, it will naturally flow downstream. Additionally, the volume increases when microplastics join the plastic waste in landfills. Miniature plastics have also been found in fish, indicating the widespread distribution of microplastics. The impact of microplastic damage can vary according to color, size, and type due to the presence of numerous chemicals. A single plastic item can contain at least 13 thousand chemicals.”

According to him, the current processing of plastics for recycling is unscientific because they are not separated according to color and type. Management activities are not properly conducted even in developed countries. Old plastics are recycled, and new chemicals are added to them, perpetuating environmental damage and impacting public health. The issue of pollution becomes cyclical.

Professor Dr. Abu Jamil Faisal, President-elect of the Public Health Association of Bangladesh, told Banik Barta, “There are even smaller particles called nanoplastics, which are mixing with food and entering the air. Subsequently, they are inhaled into human lungs and bloodstream. Nanoplastics can potentially contribute to lung cancer due to their harmful chemicals. Their presence in human blood can lead to various diseases and hormonal changes, affecting behavior and reproductive health.